“Even Wars Have Laws,” Mr. Allan Mukuki, lecturer at the Law School, would often remind us as we began our journey into the study of International Humanitarian Law (IHL). One of the first concepts we learned in IHL was that wars are governed by a set of rules. These rules exist to limit how wars are fought and to reduce the suffering caused by armed conflict, protecting those not involved in fighting.

The Simulation

If this simulation mirrored a real war, I can confidently say that the group we selected to carry out coursework at the beginning of the semester would not be drafted, for a glaring reason we only realised on the day of the simulation: all 10 of us wear glasses.

The simulation started with us being divided into two groups. The first, training on everything we had learnt in class—that wars have laws and these laws are meant to be respected and observed in the midst of hostilities; as well as the roles different institutions play in times of conflict. Meanwhile, because all we could hear was rapid and continuous “gunshots” and screaming from the next room, the realisation that this was not another classroom scenario became clear: we were about to pick up arms. We were about to be shot at.

During the training, the physical room was divided into two sections using tape. These sections represented the two options we would have in the different scenarios provided to us. The set-up compelled one to make a decision based on the principles learnt in class. We had to decide on the right thing to do, both as combatants and Red Cross Employees in times of war. The conflicting scenarios put us in a difficult position. Take for example the scenario that had a bit of contestation while being discussed during the simulation; if you were faced with a child soldier who has been trained to assassinate, who has done so in the past and sees you as just another target, raising their weapon towards you, would you be able to kill them?? IHL permits this given that anyone who takes up arms is directly engaging in hostilities and in such a scenario even a child would be killed. In the reality of war, showing sympathy or hesitating can lead to losing the war and putting fellow combatants at risk of death. However, in a classroom setting, where you’ve learned about these realities, it’s easier to take a side on paper.

Even Wars Have Laws

In the war room, we had rules; under no circumstance would you take your headgear off and allow a distance of five metres between you and your target. Suddenly, we were instructed to enter the room. Almost immediately, ‘gunfire’ erupted, and volunteers, who had agreed to act as victims, began screaming. The room filled with sounds mimicking the chaos of a real-life conflict, shattering the carefully laid plans we had made before entering. The situation descended into utter chaos.

Before entering the room, we had a game plan. We had read the student write-up from the simulation, and from previous class discussions we knew the principles of IHL: i) proportionality, ii) distinction, iii) necessity, iv) prohibition against attacking those hors de combat, and v) prohibition against inflicting unnecessary suffering. We walked in, intending to respect these principles. We understood our roles clearly before entering the room. It was our responsibility, according to IHL, to disarm, disable, or “eliminate” enemy combatants. We also knew who would stay behind to protect civilians from harm and who would engage directly in combat. Our team was structured with a team lead, a co-team lead, and a radio operator.

Easy to say that we didn’t use the plan as much as we thought we would. Planning is certain only in controlled environments and with a clear mind. When we realised that the paintballs hurt and that someone’s gun was firing multiple bullets at a time, it became very real. None of the scenarios we had practised in class could prepare us for the intensity of someone shooting paintballs at us. We found ourselves ducking and running, and it felt incredibly real.

We have victims who, in the face of danger, exhibit self-preservation instincts – or at least that’s what I thought. They kick in and want to run and seek refuge for themselves, and that means you can’t leave them alone if that was your allocated post to keep the civilians safe. This is especially true when you witness someone meant to be handling interrogations and assassinating enemy combatants.

It’s hard to stick to the plan when everything around you seems to be constantly changing and your life and others are constantly on the line. Any slight change or adjustment might cost you everything and there are no breaks in between to try and get back on track. Everything seems to be happening so fast and your reaction never seems fast enough, and you can never be everywhere at the same time. The only thing you can control in that situation is what you do and what you are meant to do.

We encountered victims whose self-preservation instincts kicked in when faced with danger – at least, that’s what I believed. They wanted to run and find safety, which meant we couldn’t leave them alone, even if it wasn’t our assigned role. This was particularly challenging when we saw someone who was supposed to be handling interrogations and assassinations in the same situation.

Conclusion

In class, I was a hardliner on the stance of self-preservation, and this mindset influenced how I acted in the simulation. I constantly reminded myself to assess the situation carefully, like when someone put their arms down in surrender or had a dummy gun, indicating not to shoot. However, it wasn’t easy because sometimes the threat felt real, and there was no time to confirm its authenticity.

So again, EVEN WARS HAVE LAWS.

Article written by: Tiffany Maigua, Strathmore Law Student (IHL 2023-2024)

What’s your story? We’d like to hear it. Contact us via communications@strathmore.edu

ALSO CHECK OUT

See more news-

Stratizens Triumph at Olympia Invitational Debate Tournament* 11,Apr,2024

The Strathmore Debate Society clinched monumental victories at the prestigious Olympia Invitational,

-

Bridging gender gap in healthcare* 09,Apr,2024

In Kenya, women remain underrepresented in senior positions across many sectors, including

-

Financial Literacy – What students need to know* 09,Apr,2024

With the fresh wave of high school graduates stepping into the threshold

-

THE TIGONI EXPERIENCE* 05,Apr,2024

It all started with receiving an invitation to the 2024 Tigoni Leadership

-

Even Wars have Laws: A Simulation of War* 05,Apr,2024

“Even Wars Have Laws,” Mr. Allan Mukuki, lecturer at the Law School,

-

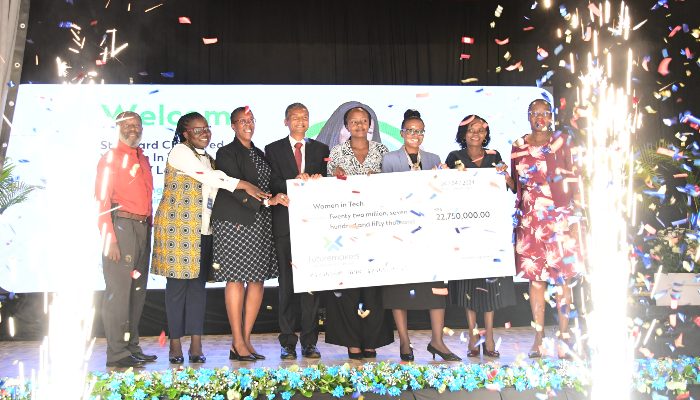

Cohort 7 of Women in Tech Launched* 04,Apr,2024

@iBizAfrica – Strathmore University in partnership with Standard Chartered Bank has launched

-

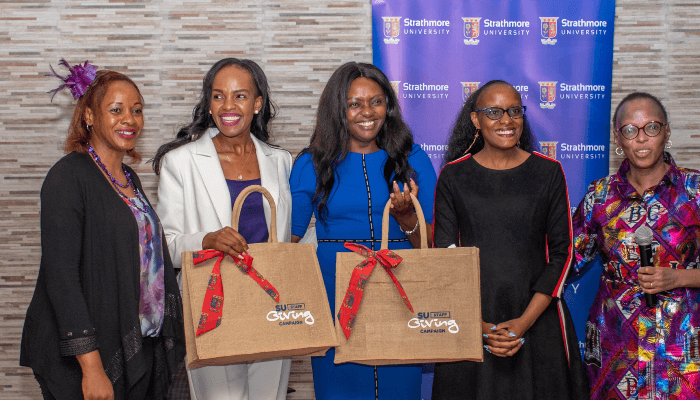

Strengthening Bonds: Strathmore Alumni Reunion in Uganda* 04,Apr,2024

On the evening of March 1, 2024, a significant gathering unfolded at

-

Nurturing Lifelong Connections: A Journey Beyond Graduation* 04,Apr,2024

Friendships forged during school life burn bright long after the caps are

-

Future proof: The School of Engineering and Computer Sciences commemorates World Engineering Day* 12,Mar,2024

The air crackles with innovative energy on Strathmore’s campus today. Engineers of

-

When your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet* 11,Mar,2024

Sitting in a room among women adorned with talent and resilience, radiating